Last updated on October 17th, 2024

Belfast’s famous Black Cab tour tells both sides of the story

by Carolyn Ray

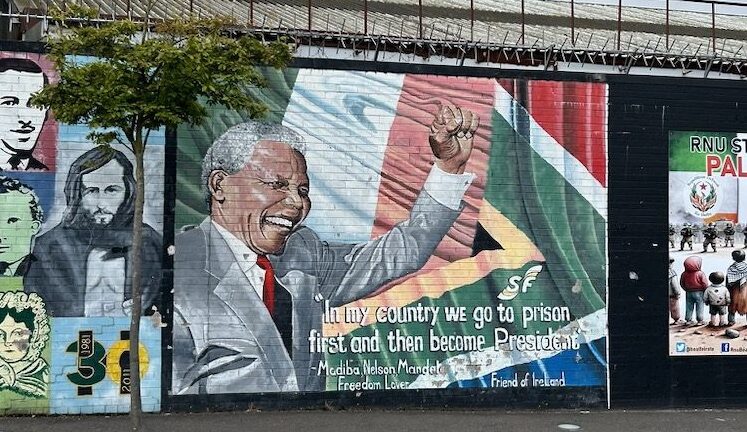

On a sunny morning in Belfast, I’m standing in front of the International Wall, the famous concrete wall that divides the city. I’m surprised to see a mural of Nelson Mandela, raising his fist into the air, alongside Irish heroes such as Bobby Sands, Kieran Nugent and Billy McKee. The caption on it reads: ‘In my country, we go to prison first and then become President’ with ‘freedom lover’ and ‘friend of Ireland’ written at the bottom. Why is Mandela, celebrated worldwide as a heroic figure, on this wall alongside Irish revolutionaries?

When I share my observation with Paul, my Black Cab driver, he tells me this that is one of the most important murals on the wall. “Was Nelson Mandela a terrorist — or was Nelson Mandela a freedom fighter?” he asks me. “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist.”

I’m surprised by this idea. But at the end of the day, after spending five hours with Paul, I realize that there are two sides to every story, and that this is more than a wall — it’s a forum to open up discussion and curate different perspectives. For Paul, this is vitally important to the peace process.

“For our peace process to continue, we must acknowledge that people have completely opposite opinions which we can debate, discuss, argue, as long as we don’t hurt each other over it,” Paul says. “This is what our peace process is all about. We must accept that people have completely opposite opinions, and they’re entitled to have them. They’re entitled to have them. Respect and dignity for all.”

Paul, who was born in Belfast and has lived here his entire life, won’t disclose his political preferences. What he will do, however, is represent both sides of Belfast’s history based on his personal experiences with the Troubles. As the son of a Belfast mother and British father, he’s experienced more than the average person. When the two married in 1945, they lived in Southampton but returned to Belfast to raise their family, never imagining what would follow.

There was a time when Paul had to leave Belfast for this own personal safety and spent three years in Canada, a fact that makes us instant friends. Like many, I have Irish heritage, but I’ve never really considered what it meant. Hearing Paul’s first-hand stories changes something in me. Not only am I more aware that we’re connected, I’m also more attuned to how much information is filtered through limited and sometimes biased communication channels to maintain the popular narrative. Like most everything, there are at least two sides to every story.

Get stories just like this delivered to your inbox! Sign up here.

The pot of milk on the stove

Ireland’s journey to independence has been centuries in the making. Paul describes it as a pot of milk on a stove, constantly heating up, then boiling over.

“This pot with the milk has been on the stove for 800 years,” he says. “Every time the milk boiled over is all the times of rebellion and trouble in Ireland. And there’s lots and lots and lots of examples of it. You just have to go back to the 1100s and follow it from there.”

In the early 1900s, Belfast was a huge industrial city. There was rope making, shipbuilding, whiskey, tobacco, and a world-class linen industry. Belfast was a very profitable city, more so than Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester or Birmingham, particularly in wartime. Even then, there was discrimination and intimidation, despite most residents of Belfast being Catholic. The white-collar jobs at the Titanic shipyards were handed down to friends and family, rather than offered to Irish-born workers, who had to line up for jobs every day. Prior to the Titanic’s 1912 launch only 400 of Harland and Wolff’s 10,000-strong workforce were Catholic. As a result of segregation in schooling, housing and employment, young Protestants and Catholics rarely mixed, socialized or married.

On Friday, August 15, 1969, the milk boiled over in Belfast when, Paul says, thousands of Protestants, unionists, loyalists supported and aided and backed by the police force (such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA)) burned Catholics out of their homes while they came down these streets to attack Falls Road, where most of the Catholics lived. The Troubles lasted for 30 years and over 3500 people were killed in the conflict.

“The Catholics had no one to protect them because the IRA were almost completely annihilated by August 1969,” he says. “It was estimated there was 12 guys with six guns in that area. They couldn’t defend themselves, never mind the area.”

The 1998 Good Friday Agreement was a major step forward in the peace process, restoring self-government to Northern Ireland.

Through the gates

The International Wall, which runs for 30 kilometres (18 miles) through Belfast, is now a tourist attraction, but was built by the British Army in 1969 to separate neighbourhoods and communities, a duty it still performs today. The graffiti that covers it reflects Irish independence on one side, and British loyalist murals on the other.

Just 12 weeks ago, new murals were painted about the Palestinian conflict on the ‘nationalist’ side of the wall, which started in the 1970s and features 10 men who died in 1981 on a hunger strike. There are images of the signatories of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, which was the start of a rebellion that went right through from the election of 1918 to the War of Independence. It’s provocative and disruptive. Another is of a red ribbon and a poem written by a university lecturer in Gaza. It shows three children in the middle: an Irish child, a Palestinian child, and a South African child, imagery that links the three struggles from those three nations together: Apartheid, Palestine and the Irish conflict.

The graffiti, Paul says, is organized and scrutinized by the community.

“If they feel it’s too offensive, they’ll go ‘no’,” he says. “The people will voice their opinions. People can voice their opinions now because we have a ceasefire.”

We drive through a set of imposing steel double gates. These were put up in 1969 and open and close as necessary. Others, Paul says, don’t open at all and are welded shut.

“There are eight sets of gates on this particular part of the wall,” he says. “Every night at 7:30 p.m. all of the gates that are open are locked and shut until tomorrow morning. There is one set in the middle of this wall that is sometimes left open to 10 or 10:30 at night. This wall is heavily covered with CCTV monitored 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

One of the dynamics that is changing Belfast, he says, is immigration.

“Since 1998, we’ve had lots of visitors, and lots of immigrants are coming here from all over the world,” he continues. ”We even have Canadians that live here. Those immigrants bring a richness to this community that helps our peace process. It dilutes the sectionalism that caused the trouble.”

For the first time since the creation of Northern Ireland, a 2022 census shows that Catholics now outnumber Protestants, with 45.7 per cent of people identifying as either Catholic or from a Catholic background, compared to 43.5 per cent who are Protestant or from other Christian denomination. Proportionally, the fastest-growing group was those of other national identities, which the statisticians said were typically identities from outside the UK and Ireland. This group almost doubled, from 61,900 people in 2011 (3.4 per cent) to 113,400 in 2021 (6 per cent).

Welcome to No Man’s land

We continue through a commercial area with small shops and warehouses.

“Now we’re in No Man’s Land,” Paul tells me. “Once we go through this area, we’ve left the Protestant Unionist Loyalist area and are now into the Catholic Nationalist Republican Falls Road.”

The change is abrupt and unsettling. Suddenly, it feels like we’re in a suburb of London. I whip my head around, looking for evidence of Ireland. Hundreds of British flags line the streets. Massive full-scale murals of Queen Elizabeth and King Charles cover the side of buildings everywhere I look. In a show of support for Israel, British flags with the Star of David are mounted on the sides of houses. Huge metal structures cover the roads, with photos of Queen Elizabeth, King Charles and William of Orange on his white horse. The “Twelfth” celebrations in July have just finished with fireworks, bonfires and parades. Also known as “Orangemen’s Day”, it’s celebrated to commemorate King William’s victory over Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne 334 years ago, which ensured Protestant control over Ireland.

Understanding the difference between a nationalist (or republican) and unionist is important, Paul tells me.

“A nationalist is a person considers themselves as Irish,” he says. “They have an Irish passport. They will have the ability to or the desire to speak the ancient language of Gaelic. They want Ireland to be reunified as one country with no input at all from England, self-governed. They will have no allegiance to the English throne and they will see their flag as the Irish tricolour with green, white, and orange.”

In the Irish tricolour flag, the green represents nationalism. The orange represents unionism because of King William III and the white is for peace between the two. Designed by an Irish American in the 1800s, it was adopted by the Irish Republic in 1916 during the Irish War of Independence.

“It is fair to say that most nationalists would be Catholic, but not all,” he says. “We have Catholic and Protestant nationalists. As example, Theobald Wolfe Tone. A more vehement nationalist can be referred to as a republican. Nothing at all like the republicans in America. Don’t get confused with that one. But that’s what a nationalist is. “

On the other hand, a unionist is someone who considers themselves as British.

“They will have a British passport,” he says. “They will have an allegiance to the English throne and they will have a very, very deep, deep-seated belief that the northeast corner of Ireland remains part of Britain. They see Belfast as British as Birmingham, Bradford, or Bristol.”

Bombay Street in Belfast

We get out of the cab at Bombay Street, known as the official starting point of the Troubles on Friday, August 15, 1969. With a shock, I realize I’m standing on the same street featured in the movie Belfast, although the houses have been rebuilt.

“This is the first street attacked by the Unionists,” Paul says. “Here, 87 families’ homes were burned in a very short space of time. This was the start of the violence. It snowballs and it literally turns neighbour against neighbour and community against community. The next night, 116 homes in the same area are burnt, and the violence just erupts.”

Behind the row of houses is an enormous wall stretching into the sky. Metal grates cover the roofs and the backs of the houses. Paul says the grates are a defence against grenades being thrown over the wall. It seems inconceivable that this could happen, and I wonder how people can live with this constant reminder of violence and aggression.

“If you ask those people in the houses, would you like that wall there, would you like those grills off, they will say yes,” Paul says. “They would like them down, but they will also say ‘not yet’ because, at the moment, they are our security blanket.”

Find a Black Cab Experience: Find local tours here.

Feeling change is possible at the Peace Wall

We end our day at the Peace Wall, the other side of the same wall that divides Bombay Street from the rest of Belfast. Tourists are gathered with markers, writing messages on the walls. Paul points out where prime ministers, presidents, celebrities and movie stars have come to sign their messages. People like Justin Bieber, Rihanna, and President Clinton.

I choose a spot close to where His Holiness the Dalai Lama wrote “Open your arms to change, but don’t let go of your values.” I spend a few minutes thinking about what to write, not wanting to be pithy. I’m also overwhelmed by the gravity of this moment.

“This peace process we have is the closest to peace this island has had in 800 years,” Paul says. “It must work. It has to work. We’ve come too far. There are too many lives that have been saved for it not to work. And it is getting there, and it will get there. Just going to take a bit of time. In the meantime, the divisions and the walls are needed.”

Carolyn signing the Peace Wall / Photo by Carolyn Ray

With Paul, a Black Cab driver in Belfast / Photo by Carolyn Ray

Hoping for peace

After spending almost five hours with Paul, I’ve come to see Northern Ireland with fresh eyes. I had never thought of Ireland as a country divided until this trip; in fact, I had never truly understood its history. And it’s not just this experience; Ireland’s history is being recast with a more accurate narrative. Everywhere I travelled to in Ireland, I see that phrases like ‘the great famine’ have been replaced with ‘the great hunger’, an acknowledgement that there was not a famine, but rather control over the food that was available. This is when millions of Irish emigrated to find a better life where they could live as they chose, without fear.

It seems that all of us with Irish blood return at some point. Even Paul, who left Belfast for a few years to live in Canada, returned to try and make a difference by sharing his story with the tourists here. After hearing his story, I understand why he, and so many others, feel gratitude for the freedom they have now. It makes me think about my own freedom, and how I take it for granted. It also makes me reflect more on my heritage, knowing that many of my ancestors came from Ireland.

“There is no guarantee that when you come back your signature will still be here,” he tells me. “But you will have the photograph. It’s important you come back.”

I can’t help but give Paul a hug, feeling the emotion of the moment. I promise him I’ll return, and we exchange emails and phone numbers. Someday, Belfast, I’ll be back. I promise.

Author’s note: There are many Black Cab tours offered in Belfast. I took Paddy Campbell’s tour, which employs both Republican and Unionist drivers. My tour was originally supposed to be 90 minutes for 50 pounds per person. However, thanks to Paul’s generosity, he extended it and even gave me a lift to the train station. You can learn more here and ask for Paul. Make sure to mention you read about it on JourneyWoman.

Tips about Belfast

Tip: On July 14, the day I arrived in Belfast, it was a national holiday weekend (‘the Twelfth’) and almost everything was closed. Check dates before you book.

Things to do: Don’t miss the Titanic Museum. This is a must-see for understanding the story of Belfast as an industrial capital in the 1900s, including its shipbuilding, rope-making, and linen industries. UNESCO World Heritage site Giant’s Causeway is a must-see (start on the lower path and then climb up to the top for incredible views). To learn more about Irish history, consider visiting EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and take the two-hour 1916 Rebellion walking tour in Dublin. Click here to find even more things to do in Belfast.

Getting to Belfast: The train or bus from Dublin takes less than two hours and is a 10-minute taxi ride to the downtown area. Check train schedules here.

Restaurants: In the downtown area, try Robinsons and McHughs Pub, established in 1711, near the tilted Albert Memorial Clock that sits on top of what was once a river. Open Friday to Sunday, St. George’s Market is one of Ireland’s oldest markets and has a Saturday craft market and Sunday antique market. Other recommended restaurants from my local host include Deane’s Meatmarket, Fibber Magges, and Stix & Stones Steakhouse.

Stay: The most vibrant area for outdoor patios and hotels was the Cathedral Quarter near Belfast Cathedral and I would spend more time there given any opportunity to return. Find a place to stay here.

More from Ireland to Inspire You

Go Your Own Way: A Self-Guided Trip to Scotland and Ireland is Full of Magical Moments

If the thought of following a tour guide on a structured itinerary isn’t your style, a self-guided trip might be the perfect solution for independent women travellers.

JourneyWoman Webinar: How To Plan a Custom Trip to Ireland and Scotland With Brendan Vacations on October 8

Join our webinar on October 8 with Ireland and Scotland experts Brendan Vacations to find out how to design your own custom trip.

Will Travel for Food: Food Tours for Solo Women

Not only do food tours give insight into a culture, they are a great way for solo women to connect with locals and other travellers.

0 Comments

We always strive to use real photos from our own adventures, provided by the guest writer or from our personal travels. However, in some cases, due to photo quality, we must use stock photography. If you have any questions about the photography please let us know.

Disclaimer: We are so happy that you are checking out this page right now! We only recommend things that are suggested by our community, or through our own experience, that we believe will be helpful and practical for you. Some of our pages contain links, which means we’re part of an affiliate program for the product being mentioned. Should you decide to purchase a product using a link from on our site, JourneyWoman may earn a small commission from the retailer, which helps us maintain our beautiful website. JourneyWoman is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases. Thank you!

We want to hear what you think about this article, and we welcome any updates or changes to improve it. You can comment below, or send an email to us at [email protected].