Last updated on November 2nd, 2023

Featured image: A Kenyan cheetah relaxes in the bush | Photo by byrdyak on Envato

How communities are working to save the vanishing cheetah from extinction

By Rupi Mangat, Contributor, Women in Africa

Mary Wykstra saw her first cheetah when she took her first zoo-keeping job fresh out of college in the USA (she had never been to a zoo until the day she went for her interview at age 22!) She was bewitched by the cheetah’s eyes, inspired by the quote: “To look into the eyes of a cheetah shows a history unknown to man.”

Today, Mary is a respected cheetah researcher, working with the communities in the arid regions of northern Kenya to ensure there are safe spaces in the wild for the spotted sphinx.

Q&A With Mary Wykstra, on Cheetah Conservation

Mary, tell us what is the current population of cheetahs in the wild in Kenya and the world? Is Kenya a stronghold?

Thank you for giving me this opportunity to share my story and the plight of the cheetah. Kenya is central to the Eastern African cheetah population and holds less than 1200 cheetahs. Surrounding countries of Tanzania, Uganda, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia each hold less than 500.

Although cheetahs do not know country boundaries, their populations are becoming fragmented by land use change and impacts of climate change that form barriers to free-ranging cheetah populations. It is estimated that the 7,000 cheetahs remaining in Africa today are dwindling at a rate of as much as 2.1% per year. Kenya holds one of the most connected cheetah populations both within the country and through the trans-boundary connectivity.

Mary with Nairobi orphanage cheetah / Photo provided by Mary Wykstra

What’s the trend in cheetah conservation been over the century?

Sadly, as with other cheetah-range countries, Kenya is undergoing rapid land use change and human settlement throughout the cheetah strongholds. Settlements and roads bring development to the human population, but fragment populations of wide-ranging species like the cheetah.

Since we began working in Kenya in 2001, the cheetah numbers have continued to dwindle. At one time it was estimated that more than 100,000 cheetahs roamed this part of the continent. They were captured as pets, killed over conflict with livestock farmers and suffered from land-use and climate change.

Despite our best efforts, all of these threats still face cheetahs today. Illegal cub trade has been on the rise in the past 10 years with demand for the cubs coming from Middle Eastern countries.

One of the biggest threats to cheetahs today is the global pet trade and marketing on social media. Tell us something about it.

The cheetah pet trade follows the same routes as ivory, rhino horn and weapons. Until recently we believed that the pet trade had dwindled, but it turns out that the pet trade is alive and well. Thanks to efforts from international partners like the Cheetah Conservation Fund and governments in the Horn of Africa have a source of information and support that has brought this ugly trade to light. CCF works with the government in Somaliland, one of the key trade routes, to confiscate cubs before they reach the market.

With my roots from CCF, I continue to work with them to assist with the development of a cheetah care center in Somaliland that now houses nearly 90 cheetahs that have been confiscated since 2016. Ongoing partnerships in Somaliland keep their finger on the pulse of the trade which is believed to originate in the Horn of Africa, possibly including Kenya. Our focus, in partnership with other organizations in Kenya, is to assure that no cubs are taken out of Kenya because once confiscated in Somaliland they will not be able to come back.

Social media is one place where cheetah cubs are marketed. Our colleagues monitor the social media outlets and send the information through channels that help to find the chain through which the cubs are sold. This often leads to confiscation, but unfortunately, many cubs are weak and sick and many do not survive. Confiscated cubs are often infected with Feline Infections Virus, a highly contagious disease, that even if survived will always be carried by the cheetah. Such cubs cannot go back into the wild even if we had the means to get them back. It is essential that our efforts in Kenya prevent cubs from being taken or transported in the first place.

Why are cheetahs so endangered?

Cheetahs suffer from the threat of extinction more than most other big cats because of poor genetics and their solitary lifestyle. At two points in history, cheetahs are believed to have suffered a bottleneck of fewer than 50 individuals – first during the Ice Age when so many species did not recover. Then again in the 1500s when cheetahs were taken as pets by royalty who used them in a hunting sport called coursing.

Now, as the world’s wildlife populations are plummeting due to the impacts of human land use and climate change, the cheetah is among those on the list of most vulnerable species.

Male cheetahs live alone or in small coalitions that are usually made up of brothers – these coalitions are usually 2-3 individuals that will stay together from birth. Occasionally, as was seen recently in the Maasai Mara – larger groups of individuals may temporarily join forces. Many people proudly followed the ‘Tano bora’ group of five cheetahs that ruled a section of the Mara for over two years. That was an unusual social grouping. Tano Bora in Kiswahili, Kenya’s national language, translates to ‘pride of five’.

Mary and a contingency from Somaliland learning about conservation area management styles in Kenya / Photo provided by Mary Wykstra

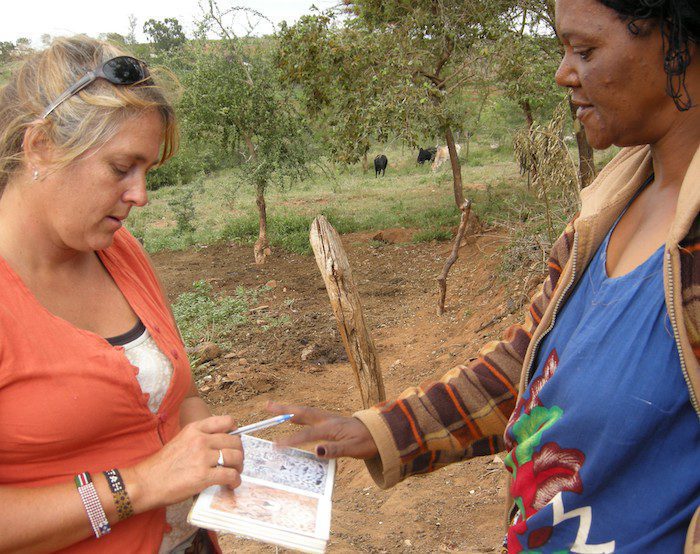

Mary talking about cheetah and leopard with a farmer after a livestock attack / Photo provided by Mary Wykstra

Female cheetahs are usually alone and raise their cubs without the assistance of a male. Cubs stay with their mother for 12-18 months during which time she teaches them all that they need to know to survive.

As a cat, they are born with an instinct to chase, but it is their mother that teaches the cubs to select the right prey, kill it correctly and eat the right parts first before other scavengers get the chance to steal the kill. The mother also teaches the cubs where to find water and that staying on the move all the time is their best chance of survival.

How did you get started in this?

I first learned about the plight of the cheetah when I was a zookeeper in the 1980s. The first time I visited a zoo and saw a cheetah was when I interviewed for the zoo-keeping job. I was hooked by the beauty and grace of the cheetah.

My favourite quote has been “To look into the eyes of a cheetah shows a history unknown to man.” The amber eyes of the cheetah reached into my heart and I knew that I had to do something. I started by fundraising, then I travelled to Namibia as a volunteer for the Cheetah Conservation Fund. It was in Namibia that I learned that cheetah biology was not the problem. It is only through community conservation that cheetahs can be saved.

I visited Kenya in the mid-1990s and saw wild cheetah for the first time in northern Kenya. In 2001, I proposed to work with the Kenya Wildlife Service (the government organization in charge of the country’s wildlife) to grow a cheetah conservation project which has now become the longest-dedicated cheetah project in Kenya. We registered Carnivores, Livelihoods and Landscapes (CaLL) as a not-for-profit company in Kenya and the Action for Cheetahs in Kenya (ACK) project was the first programme under the CaLL umbrella.

NB: JourneyWoman readers may not be familiar with the Kenyan landscape below. However, Mary’s narration shows the challenges and populations vanishing in different parts of Kenya.

From 2001 – 2004, we were based in central Kenya at the Soysambu Conservancy (Nakuru and Naivasha County) where it was hoped that we could re-establish a decimated cheetah population. Sadly, the land use change in that region was too much for a free-ranging cheetah population and we felt that a cheetah sanctuary in that area would have a negative impact on the free movement of other wide-ranging wildlife that still inhabited the farmlands.

Find a tour: Find a women-friendly safari right here on the Women’s Travel Directory

From 2005 – 2020, we worked in the Machakos and Makueni Counties where rapid land use change had already begun. The area of Makueni where we set up our base was subdivided into small subsistence plots in 2007, something that was well in the works prior to our time there. We identified about 30 cheetahs around the Salama area of Makueni, but by 2015 the population dropped to less than 5 who were transient (not resident) and passed through only a few times a year. The neighbouring Athi-Kapiti region remained a corridor that has continued to have resident cheetahs – about 25 but has also undergone development that makes barriers to free-ranging wildlife populations. Sadly, in 2020, we closed our base facility in Salama to focus on cheetahs in northern Kenya.

We initiated a three-year National Cheetah Survey in 2004, and after analyzing the data we determined that Northern Kenya had one of the most connected and wide-ranging populations of cheetah in Kenya. We began working in the Meibae Community Conservancy in 2009 and built our permanent camp there in 2015. Initially, we set up rigorous monitoring programmes and evaluations of human-carnivore conflicts to learn about the threats to cheetahs and their relationship with humans. Through the research, we initiated several community projects to simultaneously protect cheetah and human livelihoods.

Mary with youth in Meibae / Photo provided by Mary Wykstra

And why are you so focused on partnering with local communities?

From my days in Namibia, it was very clear that no amount of science in the world could save the cheetah without the efforts of the people who live with wildlife. Our entire staff is Kenyan and more than 50% are from the community that we work in. It is essential not only to understand the biology and ecology of the cheetah but also the indigenous knowledge and the culture that has held the cheetah within its community for centuries. There are areas of development that when done sustainably, can benefit both the cheetah and the people. It is our goal to not lead the people but to guide them in the direction of common values. Conservation is essential for the pastoral way of living – without grass there will be no cattle, no goats or camels and no elephants, gazelles or cheetahs.

We try to reach all of the audiences of people who can assist in cheetah conservation. We work with women’s groups in environmental caretaking, with youth through sporting events (International Cheetah Day football tournament, and with elders through community meetings). We work with young herders who are not a part of the typical school system through end-of-day and Saturday events like movies and games. During the drought, we assisted needy families with food supplies at a time when they needed it most. So much of our work revolves around the people who in turn provide freedom to the cheetah.

One of your recent works is collecting cheetah poop? Why?

The cheetah is a very sensitive animal which is in low numbers. Invasive monitoring methods like collaring and blood collection require immobilization, which is not ideal when a population is so low.

We have chosen to use non-invasive monitoring methods. We selected a monitoring method that includes a combination of social surveys (asking people about the cheetahs they see), patrol-based surveys (recording what we see – tracks and signs – like prey base), and the use of scat detection dogs. Scat (the scientific name for poop – and lovingly referred to as our ‘black gold’) tells us so much about the cheetah – its diet, its health and its genetics. We learn all of this without ever touching the cheetah!

Understanding the cheetah diet helps us to know which prey is needed in each area for cheetah populations to remain healthy. The diet also tells us how often cheetahs kill livestock, thus causing conflict with the local pastoralists and farmers. This, in turn, helps us in mitigating said conflicts to reduce the cheetah’s impact on human livelihoods.

Understanding cheetah health lets us know if the cheetah has a high parasite or virus load in the wild. Cheetahs are susceptible to pretty much any disease that infects domestic cats or dogs.

As a part of disease monitoring and management, we initiated a domestic pet vaccination programme that has since vaccinated nearly 4000 dogs and cats annually. This year we are working with our partners to test the level of protection against distemper in the dog population by sampling dogs in 3 regions where the vaccination campaigns have been ongoing. We named our campaign “Ginger’s Hope” after our first scat detection dog in the hope that all dogs can live a safe and happy life as she did.

Mary with the canine team and advisor Dr. Willis after searching for cheetah scat in northern Kenya / Photo provided by Mary Wykstra

In the wild, what must we NOT do when we see a cheetah?

Cheetahs are shy and elusive animals – it is a great pleasure when they allow us to see them in their glory. Herders should shout and throw stones in the direction of a cheetah if they feel that the cheetah is a threat to their livestock. But if we are on a safari, we should behave just the opposite. We should keep our voices low. We only hoot our horn if we find a cheetah approaching our vehicle. Cheetahs love to climb on high objects, but vehicles are slick and may cause a cheetah to slip and injure itself when jumping up or down.

NB: Keep a distance away from wild animals. Instead, use your binoculars to watch them – it doesn’t stress them out.

If you see a cheetah when you are on foot you should not turn your back or run, face the cheetah, speak loudly and waive your arms to frighten it away. Never run from a predator of any size.

How do you help share your passion with future generations?

Outside of the community awareness programmes I have been helping to coordinate and/or lead several types of safaris. We bring students from my hometown secondary schools to develop a relationship with a local secondary school in a week-long programme that was initiated in 2012. Students make lifelong and life-changing relationships that have guided them in paths of conservation, education and medical careers. In 2015, we initiated an Adventure Safari led by members of my US board – in this safari, people do some traditional safari things but culminate the trip with several days at our field site camping, assisting with research and getting to know our community.

Finally, in 2020 I began co-leading a learning course from George Mason University where we delve into the issue of protected area and community land and wildlife management and in 2023, I am co-leading a course from Colorado State University on animal behavior and ecology. The next will be to include Kenyan university students in the courses and hope to make it a credited course at the University of Nairobi as well.

Mary with George Mason study abroad students / Photo by Mary Wykstra

Mary and ACK field officer Kivoi in Meibae / Photo by Mary Wykstra

Through these courses, not only do I get to introduce people from my home country to the joy and beauty of Kenya and the cheetah, but to gift Kenya with the opportunity to meet some amazing people as well. My staff love to interact with people of different cultures, so I think it is a good experience for everyone involved to get to know someone and some things that are new to them.

What’s your hope for the future?

As the director of Action for Cheetahs in Kenya, I believe in our mission to promote the conservation of cheetahs through research, education and community engagement. I see a future where community conservation and protected areas work in harmony to maintain regions where cheetahs can thrive.

While it is a high hope that we can maintain corridors that allow cheetah population stability, this is what we work for at Action for Cheetahs – by understanding current connectivity and valuable corridors we will assist in the management and protocols needed to promote a healthy and sustainable cheetah population across Kenya as a model for other regions.

Please visit www.actionforcheetahs.org and follow it on social media.

Watch out for Mary’s annual trip to the US where you may have a chance to meet her and learn the current challenges of cheetah survival.

Read More From Rupi and Women in Africa

Meet the Woman Protecting Zimbabwe’s Majestic Lions: Moreangels Mbizah, the only Indigenous Black Woman Lion Conservationist in Zimbabwe

Across Africa, many communities feel alienated from wildlife, but through the efforts of Moreangels Mbizah, this perception is changing.

How Travel Changes Us: From Grieving Widow to Cheetah Crusader in Kenya

When Michele McCarthy was widowed, she turned to solo travel as a way to reinvent herself as a cheetah crusader in Kenya.

Dr. Shirley Strum: Walking with Baboons in Kenya

Meet Dr. Shirley Strum, founder of Uaso Ngiro Baboon Project in Kenya, who has created baboon eco-tourism projects at Twala-Tenebo Cultural Village to employ women in Kenya.

0 Comments

We always strive to use real photos from our own adventures, provided by the guest writer or from our personal travels. However, in some cases, due to photo quality, we must use stock photography. If you have any questions about the photography please let us know.

Disclaimer: We are so happy that you are checking out this page right now! We only recommend things that are suggested by our community, or through our own experience, that we believe will be helpful and practical for you. Some of our pages contain links, which means we’re part of an affiliate program for the product being mentioned. Should you decide to purchase a product using a link from on our site, JourneyWoman may earn a small commission from the retailer, which helps us maintain our beautiful website. JourneyWoman is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases. Thank you!

We want to hear what you think about this article, and we welcome any updates or changes to improve it. You can comment below, or send an email to us at [email protected].